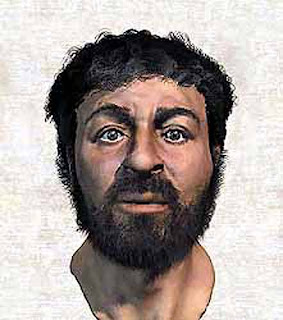

Will the real Jesus please stand up?

The following is an address prepared for a service at Chester recently which ended up being a discussion instead so was never delivered.

I remember a comedy car sticker from

the eighties that was supposed to be funny but always worried me. It read,

'Jesus is coming back: Look busy.' We probably all know what this meant. It was

a reference to this idea of an end of history, a judgment day, when according

to some, Jesus was going to come back as a kind of warrior king, rewarding

those who followed him and condemning the rest. It was an idea that I found,

and still find, pretty unsavoury, and it seemed a long way removed from the

Jesus of my earlier childhood, the man from Nazareth who talked about

forgiveness and equality, the man so often referred to as the 'Prince of

Peace.'

I remember a comedy car sticker from

the eighties that was supposed to be funny but always worried me. It read,

'Jesus is coming back: Look busy.' We probably all know what this meant. It was

a reference to this idea of an end of history, a judgment day, when according

to some, Jesus was going to come back as a kind of warrior king, rewarding

those who followed him and condemning the rest. It was an idea that I found,

and still find, pretty unsavoury, and it seemed a long way removed from the

Jesus of my earlier childhood, the man from Nazareth who talked about

forgiveness and equality, the man so often referred to as the 'Prince of

Peace.'

I remember a comedy car sticker from

the eighties that was supposed to be funny but always worried me. It read,

'Jesus is coming back: Look busy.' We probably all know what this meant. It was

a reference to this idea of an end of history, a judgment day, when according

to some, Jesus was going to come back as a kind of warrior king, rewarding

those who followed him and condemning the rest. It was an idea that I found,

and still find, pretty unsavoury, and it seemed a long way removed from the

Jesus of my earlier childhood, the man from Nazareth who talked about

forgiveness and equality, the man so often referred to as the 'Prince of

Peace.'

I remember a comedy car sticker from

the eighties that was supposed to be funny but always worried me. It read,

'Jesus is coming back: Look busy.' We probably all know what this meant. It was

a reference to this idea of an end of history, a judgment day, when according

to some, Jesus was going to come back as a kind of warrior king, rewarding

those who followed him and condemning the rest. It was an idea that I found,

and still find, pretty unsavoury, and it seemed a long way removed from the

Jesus of my earlier childhood, the man from Nazareth who talked about

forgiveness and equality, the man so often referred to as the 'Prince of

Peace.'

I decided to talk about Jesus today

because I consider myself a Unitarian Christian. My spiritual journey has

evolved over time but instinctively I have kept Jesus at the centre and I think

I always will. In talking about Jesus I am, of course, getting to the heart of

what Christianity is all about. It is interesting to note that in Judaism the

decisive revelation of God is considered to be found in a book, the Torah and

similarly Muslims consider the Qur'an to be the decisive revelation with

Muhammed being the revealer but not the revelation itself. In Christianity,

however, the decisive revelation of God's character is not the written word but

a person – Jesus. That, I think, can be both liberating and constricting. It's

liberating because it suggests that what matters is a relationship rather than

obedience to a prescribed set of rules. Any kind of healthy relationship allows

a person to be, to a large extent, themselves and that is how it is with Jesus.

Read the gospels and you see a pattern of Jesus meeting people where they are,

whether they are important interpreters of religious law, tax collectors,

fishermen, prostitutes or whoever else. In the world view of Jesus, everyone is

a person of worth, everyone matters, everyone can be themselves and Jesus won't

behave as if they are beneath him. On

the other hand the idea of Jesus as the decisive revelation of God's character

is tricky because many Christians feel unable to be properly critical of some

of the claims made for Jesus. This is

the Christian holy-of-holies and messing with it seems profoundly dodgy.

Here's my problem, and bear in mind I

am speaking only from my own experience and no one has to agree. One of the

barriers in my own faith journey has been that ever since my adolescence, I

have been aware of at least 3 different versions of Jesus in the bible and my

view has been further fogged over the years by the different claims made for

him by people coming from different theological and political positions. I am

indebted to Dr Andrew White, who I heard recently speaking on a Unitarian

podcast recorded in Quincy, Illinois who explored the very issue that I am

talking about today. He teaches New Testament at an American college and he was

referring to the fact that many of his students attend his courses with very

little knowledge of the gospels but very fixed ideas of who Jesus was, based

less on the bible than the cultural values they have grown up with. He says

that when he asks students who they think Jesus was they tell him that he was

white, he talked a lot about ethics, particularly those revolving around sexual

purity, he opposed abortion and gay rights and his main message was believe in

me or go to hell. Doesn't that sound terrible? And doesn't something within you

say that can't be right and recognise it as a contemporary cultural obsession

rather than any kind of eternal truth? It's an uninformed mindset that scholars

readily dismiss but it illustrates the extent to which the real Jesus, insofar

as it is possible to get to him, has been lost amidst centuries of cultural

baggage with which we have weighed him down. As I said I grew up with 3 Jesuses

– the first was a human being who spoke about social justice and cared for

people – the pre-Easter Jesus if you like. The second was post-Easter, a Jesus

who had risen from the dead, who was recognizable but not recognizable, human

but able to walk through walls, a Jesus I could only really make sense of

symbolically. The third Jesus was very different – he was a warrior king, the

one from the car bumper sticker I mentioned earlier, the one who would judge

people and who was used by people I met to judge others. Andrew White referred

to this version of Jesus as faith reduced to fire insurance against hell with

Jesus being the policy product.

White also referred to six main

literary sources that contributed to the portrayals of Jesus we get in the

bible, from Q, which does not survive but is a clear influence on the early

gospels and emphasizes the more human aspects of Jesus right through to the

warrior king language of texts like Revelation. It seems to me that the process

of telling stories and making claims about Jesus over time has been like a game

of Chinese whispers. I’m sure everyone has played Chinese whispers. One person

whispers something in someone else’s ear, and they whisper to the next person

and so on and so on. Thus you start out with ‘Jim is wearing blue trousers

today’ and you end up with ‘Tim is swearing very loudly okay.’ In the process

of remembering Jesus, I feel this kind of process may have happened. In early

texts, we see a very human Jesus, with no claim of a virgin birth or being

raised from the dead, a Jesus with a lot to say about social justice, right

relationships, and fairness. In subsequent texts Jesus appears more divine and

less human. By John, divinity looms larger than humanity, with Jesus making 46

‘I am’ statements, each referring to his divine status in some way.

What I don't want to suggest is that

all of these later ideas about Jesus have no value. I must confess to being

completely put off by the warrior king of Revelation, not least because that

Jesus seems so very far removed from the Jesus of earlier texts. Perhaps this

Jesus is more a fantasy scenario for early followers of Jesus than a prophecy

of things to come. The Post-Easter Jesus texts make more sense to me in a

symbolic way. Indeed, I think there is something profound about this idea of

Jesus as simultaneously human and somehow divine that attracts me to this day

but it works for me in large part because I don't take it literally. So, for example, I don't want to stop

celebrating Easter because I've moved to the Unitarians. I might not believe in

a literal resurrection but I see tremendous value in this story of life

overcoming death, hope triumphing over despair, and love overpowering hate. It

has inspired Christians for 2000 years and continues to inspire me. That Easter

story is echoed in the natural world in the coming of spring, when through an

annual miracle of nature, life springs in places where there did not appear to

be any sign of life just a few weeks before – hope in a hopeless situation.

I love the Easter story as a story but

for the most part I draw my inspiration from the pre-Easter Jesus. The issue of

divinity I would explain in this way – Jesus was a human being, sharing all the

frailty of the human condition. He lived and died as all people do but human

though he was, Jesus is, for me, the ultimate example of what the God-filled,

spirit-filled, or love-filled life looks like. I think we see this most clearly

in the early accounts of Jesus. I think of the Jesus of Mark's gospel, a

reluctant messiah in many ways, a human being crying out to God from the cross.

I think also of aspects of the Jesus story we find in Luke's gospel, a Jesus of

social justice who advocated an upside down kind of kingdom in which the last

would be first and the first last. This is a radical Jesus, challenging us to

think about our own role in making our communities and our world better and

fairer. It is a vision of Jesus that is at the heart of liberation theology, a

way of thinking that invites us, to coin a phrase, to recognise the face of

Christ in the poor and oppressed.

This Jesus, this radical, loving human

being whose life experiences included times of sorrow and times of despair is a

person I suspect we can all respond to with warmth. More importantly this Jesus

challenges us to lives of radical love in action. But so much of the time, that

Jesus is lost in the fog of many of the claims that people have made about him

so that the dominant issues in much of the discourse about Jesus is on themes

such as the virgin birth, the existence of evil spirits or the idea of the

warrior hero who may return at any moment to judge us all.

In his talk on Jesus, Andrew White

made the very good point that as far as possible we should try to reclaim the

teachings of Jesus and distinguish

these from other people's teachings about

Jesus. I remember years ago someone telling me that it was wrong to pick and

choose what to believe when it came to Jesus. It was either all right or none

of it was but that seems a smokescreen to me. It seems to me that the Jesus who

lived and breathed on planet earth would probably be baffled by virgin birth

stories circulating about him. As a human being, he may have felt very closely

connected to God but would he have thought of himself as God or were those

words put into his mouth by a later author aiming at a different kind of truth?

And would Jesus really have recognised himself as a person obsessed with sexual

ethics? I suspect not but I recognise that even raising these questions in some

churches would get me in trouble. Andrew White has faced the same problem

teaching New Testament and offers students the following story:

Two men are talking about how much

they love their wives. The first says, 'When she was younger, my wife won Miss

World, she went on to be a film star, and she made some really shrewd business

decisions and now she has millions. She's loaded and that's why I love her.'

The second man says, 'My wife and I don't always get along. Sometimes we argue

a little bit and we need to get away from each other. Still, I don't know how

she does it but she always seems to know when I need time to be alone, when I

need to talk and when I need a hug and I try to do the same for her. She's my

companion on the road of life and that's why I love her.'

The obvious question is which man

loves his wife the most? The one who was

all about what people see, the superficial details, the appearance of wealth or

the one who recognized that his relationship with his wife was not perfect but

who appreciated the way in which his life was fulfilled by those moments he

shared with her that did make sense.

An evangelical preacher might ask how

your relationship with Jesus is and in a different way I pose the same question

today. Are we put off engaging with the Jesus story by all the baggage that has

crowded around it? How well do we really know Jesus?

Perhaps it's time to try to get back

to the teachings of Jesus rather than the many conflicting stories and

doctrines about Jesus. Less of Jesus the judge, the post apocalyptic character

to be feared, and more of that remarkable, loving man of 2000 years ago, who

met people where they were and whose story still meets people where they are, whose

life and ministry continues to change the lives of millions, who earned the

title 'Prince of Peace.'

A Reading: Nick Cave on

Mark:

The Christ that the Church offers us,

the bloodless, placid 'Saviour' – the man smiling benignly at a group of

children, or calmly, serenely hanging from the cross – denies Christ His

humanity, offering us a figure that we can perhaps 'praise' but never relate

to. The essential humanness of Mark's Christ provides us with a blueprint for

out own lives, so that we have something that we can aspire to, rather than

revere, that can lift us free of the mundanity of our existences, rather than

affirming the notion that we are lowly and unworthy. Merely to praise Christ in

His Perfectness, keeps us on our knees, with our heads pitifully bent. Clearly

this is not what Christ had in mind. Christ came as a liberator. Christ

understood that we as humans were for ever held to the ground by the pull of

gravity – our ordinariness, our mediocrity – and it was through His example

that He gave our imaginations the freedom to rise and to fly. In short, to be

Christ-like.

From Revelations: Personal responses to the Books of the Bible (2005).

Comments

Post a Comment